LEADERSHIP CRISIS

AND A STEADY SPIRITUAL COMPASS

There is a crisis of leadership in the world today.

The crisis arises from the fact that most of our business and political leaders have lost their moral and spiritual bearings.

Do you believe that modern leaders have lost their True North?

We aver that a steady spiritual compass—anchored in the universal moral values—is sorely needed for the leaders to stay the course.

Which values can be designated as universal moral values?

Harmlessness—be kind in thought, word, and deed.

Honor—honor yourself, honor each other, honor the planet.

Contribution—by contributing more than we consume, we redeem our existence.

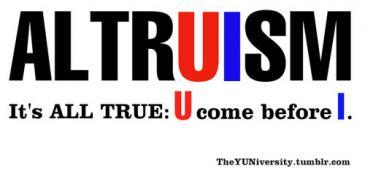

Altruism— bring the organizations forward acting for the good of others.

Humility—by putting others first, we empower them to learn and lead.

Research shows that best leaders are humble leaders and that altruism predicts a high sense of belongingness by fostering inclusiveness and team citizenship.[1]

What values do you consider to be universally prized?

The following free-flowing, interpretative translation of Lao Tzu’s wisdom captures the essence of leadership splendidly:

Learn from the people

Plan with the people

Begin with what they have

Build on what they know

Of the best leaders

When the task is accomplished

The people will remark

We have done it ourselves.[2]

How does putting others above self help to effectively lead a team and/or an organization?

Is there any evidence to show that as humans we are wired for altruism?

Dr. Edward O. Wilson, renowned biologist, ecologist and Professor Emeritus at Harvard University, explores this idea in his new book The Social Conquest of Earth.[3] The book raises several questions about the evolution of altruism. Can true altruism even exist? Is generosity a sustainable trait? Or are living things inherently selfish, our kindness nothing but a mask?

Wilson highlights the idea that we humans are extremely group-oriented with a deep desire to belong and an intense interest in what others are thinking and doing. This explains the explosion of social media, which provides the perfect venue to learn what others are thinking and doing while trying to bond through common interests and contribute to a cyber-community.

Similarly, Matthieu Ricard in his recent book titled Altruism: The Power of Compassion to Change Yourself and the World presents a vision revealing how altruism can answer the key challenges of our times: economic inequality, life satisfaction, and environmental sustainability. With a rare combination of the mind of a scientist and the heart of a sage, he makes a robust case for cultivating altruism—a caring concern for the well-being of others—as the best means for simultaneously benefiting ourselves and our global society.

Ricard concludes the book with a clarion call: “For things truly to change, however, we must dare to embrace altruism. Dare to say that real altruism exists, that it can be cultivated … and that the evolution of cultures can favour its expansion. Dare to teach it in schools… Dare, finally, to proclaim that altruism is not a luxury, but a necessity.”[4]

Even when altruism were not necessary for ensuring the well-being of others, it will still be essential for one’s own well-being. For only those who serve are truly happy.

Gandhi put it so well: “The best way to find yourself is to lose yourself in the service of others.”

This is what separates the Good from the Great in life and leadership.

——————————X—————————————X———————————–X——————————

[1] See Jeanine Prime and Elizabeth Salib, The Best Leaders are Humble Leaders, Harvard Business Review, May 12, 2014.

[2] As Quoted in Richard Pascale, Jerry Sternin, and Monique Sternin, The Power of Positive Deviance: How Unlikely Innovators Solve the World’s Toughest Problems (Boston: Harvard Business Review Press, 2010 ), 193. [Emphasis added]

[3] Edward O. Wilson, The Social Conquest of Earth (New York: Liveright, 2013)

[4] Matthieu Ricard, Altruism: The Power of Compassion to Change Yourself and the World, trans. by Charlotte Mandell and Sam Gordon (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2015), 691.

Recent Comments