TWO BIRDS ON A TREE

WHO AM I?[1]

When a question is asked, “Who Am I?” what does the word ‘I’ refer to?

The word ‘I’ can be used in three different senses.

It can refer to:

1) the body-mind complex, or

2) the ego (ahaṅkāra) or

3) the self (ātmā)

A clear distinction of these three is essential to understand and assimilate any spiritual teachings, especially Vedānta.

For simplicity, let’s call them the body, the ego, and the self. The word ‘I’ can denote any one these three meanings, depending upon the context.

For example, when I say, “I am tired,” it refers to the body-mind complex part of the ‘I.’ Similarly when I say, “I have a low/ high self-esteem, it is the ego part of the ‘I’ that is pointed out. Finally, when the scriptures tell us, “You are That (Tat Tvam Asi) or you are perfect (puraṇa), it is the self-part of the composite ‘I’ that is indicated.

Much confusion on the spiritual path can be avoided by keeping this vital distinction in mind.

So far, so good.

To understand the import of this distinction further, let’s denote these three ‘I’s as follows:

- The body-mind complex (Reflected Medium or RM)

- The ego (Reflected consciousness or RC)

- The self (Original consciousness or OC)

Let’s use the illustration of ‘electric bulb-electricity’ to make things more clear. In this analogy, the bulb corresponds to the reflected medium, the light reflected by the bulb denotes the reflected consciousness, and the electricity refers to the original consciousness.

Based on this analogy, we can draw some corollaries, as follows:

- The original consciousness (or electricity) requires a medium (or bulb) to manifest.

- The original consciousness (or electricity) pervades the medium (or matter) and enlivens it (in the form of reflected consciousness).

- The original consciousness (or electricity) is not confined to the boundaries of the reflected medium, although it seems that way.

- The original consciousness (or electricity) continues to exist even when the bulb or its reflected light ceases to be.

It is in this sense, Vedānta says that the self is immortal and eternal (avayam and nitya).

The original consciousness or self is also called the witnessing I-principle/consciousness–sākśi-chaitanya.

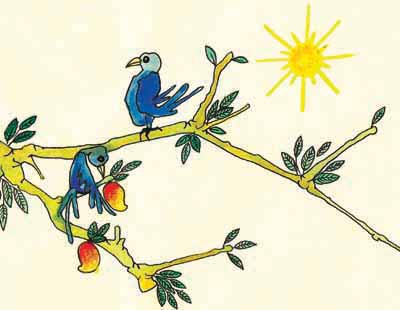

TWO BIRDS ON A TREE

द्वा सुपर्णा सयुजा सखाया समानं वृक्षं परिषस्वजाते ।

तयोरन्यः पिप्पलं स्वाद्वत्ति अनश्नन्नन्योऽभिचाकशीति ॥ १ ॥

dvā suparṇā sayujā sakhāyā samānaṁ vṛkṣaṁ pariṣasvajāte |

tayoranyaḥ pippalaṁ svādvatti anaśnannanyo’bhicākaśīti || 1 ||

Muṇḍaka Upaniṣad 3.1.1 speaks about two birds living together, perch upon the same tree. Of these two, one (the ego) eats the sweet fruit of the tree, but the other (the Self) simply looks on without eating.

Here in this analogy, the tree is the body-mind complex, the medium. The first bird represents the ego (the reflected consciousness or the jivātmā) that identifies with a particular tree, the body-mind complex, and considers itself doer-enjoyer (kartā-bhoktā) of actions (karma). The other bird, which is original or pure consciousness or the Self, does not identify itself with any particular tree-body-mind complex, not being a doer of actions is therefore free from the results of the actions, karamphalas. It merely witnesses everything that is going on! It is the witnessing-consciousness, sākśi-chaitanya.

That is the real meaning of the word ‘I.’ So, who am I?

I am the pure consciousness, or the conscious-I principle that witnesses the proceedings of the play of life, lilā.

HITTING THE TARGET

How can we attain a steady abidance (nīsthā) in this state of pure, original consciousness which the Upaniṣads tell us is our essential nature?

Muṇḍaka Upaniṣad 2.2.3 uses another analogy of bow and arrow to help us prepare for this blessed state:

धनुर्गृहीत्वौपनिषदं महास्त्रं शरं ह्युपासानिशितं संदधीत ।

आयम्य तद्भावगतेन चेतसा लक्ष्यं तदेवाक्षरं सोम्य विद्धि ॥ ३ ॥

dhanurgṛhītvaupaniṣadaṁ mahāstraṁ śaraṁ hyupāsāniśitaṁ saṁdadhīta |

āyamya tadbhāvagatena cetasā lakṣyaṁ tadevākṣaraṁ somya viddhi || 3 ||

Holding the great bow of Upaniṣadic wisdom (oṁkāra), the aspirant should fix the arrow of mind, sharpened by upāsanā, meditation, on its target. Draw the string with full absorption and shoot at the target. O my friend, remember immutable, eternal Truth alone is the target.”

The arrow has to be straight (pure mind), sharp (mind that has ekāgartā), and well-directed: to the one and the only one goal—the Brahman. Only then it will be able to pierce the target (lakṣa-bhedan).

And finally, Muṇḍaka 2.2.4 brings it all together—the traveller, the path and the goal:

प्रणवो धनुः शरो ह्यात्मा ब्रह्म तल्लक्ष्यमुच्यते ।

अप्रमत्तेन वेद्धव्यं शरवत्तन्मयो भवेत् ॥ ४ ॥

praṇavo dhanuḥ śaro hyātmā brahma tallakṣyamucyate |

apramattena veddhavyaṁ śaravattanmayo bhavet || 4 ||

“Oṁ is the bow, ātman (individual self) is the arrow; Brahman (universal self) is the target. Aim precisely and, like an arrow become merged with the target.”

…नानक लीन भयो सतगुर सो, जीओं पानी संग पानी…

[1] Primarily based on Swami Paramarthananda ji’s discourses on Muṇḍaka Upaniṣad and Tattvabōdha.

Recent Comments